Avish Vijayaraghavan

Reflections on Rudin's interpretability classic

Is this the end of deep learning as we know it?

Contents

Paper Summary

In “Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead”, Prof. Cynthia Rudin argues that explainable machine learning (EML/XAI) and interpretable machine learning (IML) are distinct fields, and that we should prioritise IML models for high-stakes decisions [1]. Rudin defines an IML model as a model which has intrinsic domain-specific constraints for solving certain tasks (e.g. model decomposability into sub-models). XAI is a separate but related field that deals with explaining “black box models” - models that humans cannot understand directly since they are derived from data without explicit description of how features are combined. The difference between IML and XAI can be summarised as: XAI is using a black box model then explaining it with another model, whereas IML is not using a black box, and instead using a model that explains itself. Rudin argues that IML models are more transparent which makes them easier to troubleshoot. This does not mean that interpretable models are never wrong, but if they are giving sub-optimal predictions, it is easier for us to understand why and recalibrate. Conversely, the reasoning within XAI models is opaque and Rudin describes the issues that arise from this.

In XAI models, explanations cannot have perfect fidelity with respect to what the original model computes because if they did, they would be equivalent to that model (making the original model interpretable). As such, any explainable method runs the risk of being an oversimplified or inaccurate representation of the original model in parts of feature space. Rudin takes the example of criminal recidivism prediction - whether past offenders are rearrested within a certain timeframe after being released. Generally, recidivism models depend on age and criminal history but issues arise because these features are correlated with the sensitive feature of race in most available datasets. This means that the explanation “this person will be rearrested because they are black” would be accurate since it replicates the predictions of the original model (i.e. whether the person gets rearrested). However, it is not a valid explanation for why someone will be rearrested, and in this case, is particularly harmful because it perpetuates racist stereotypes.

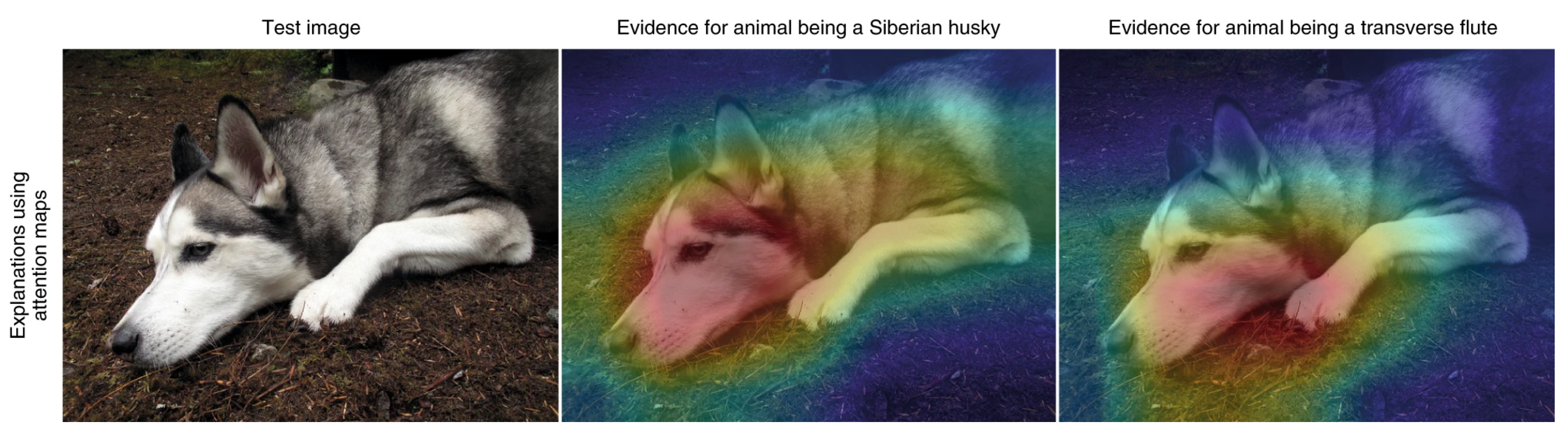

XAI grew out of work on function approximation in the 1980s which aimed to find simpler functions that preserved the main qualities of a complex higher-order function. Similarly, XAI models consist of two models: a complex black box model (usually a neural network) and a post-hoc model that computes derivatives or aims to understand the inner mechanics of the black box to determine which part of the data is being used. However, this presents another limitation of XAI - knowing which part of the data the black box is using does not necessarily tell us how it uses that part. This issue is illustrated clearly in Figure 1, we see that an explainable method, attention maps, are very similar for two obviously different concepts - a Siberian husky and a transverse flute - calling into question the utility of these methods.

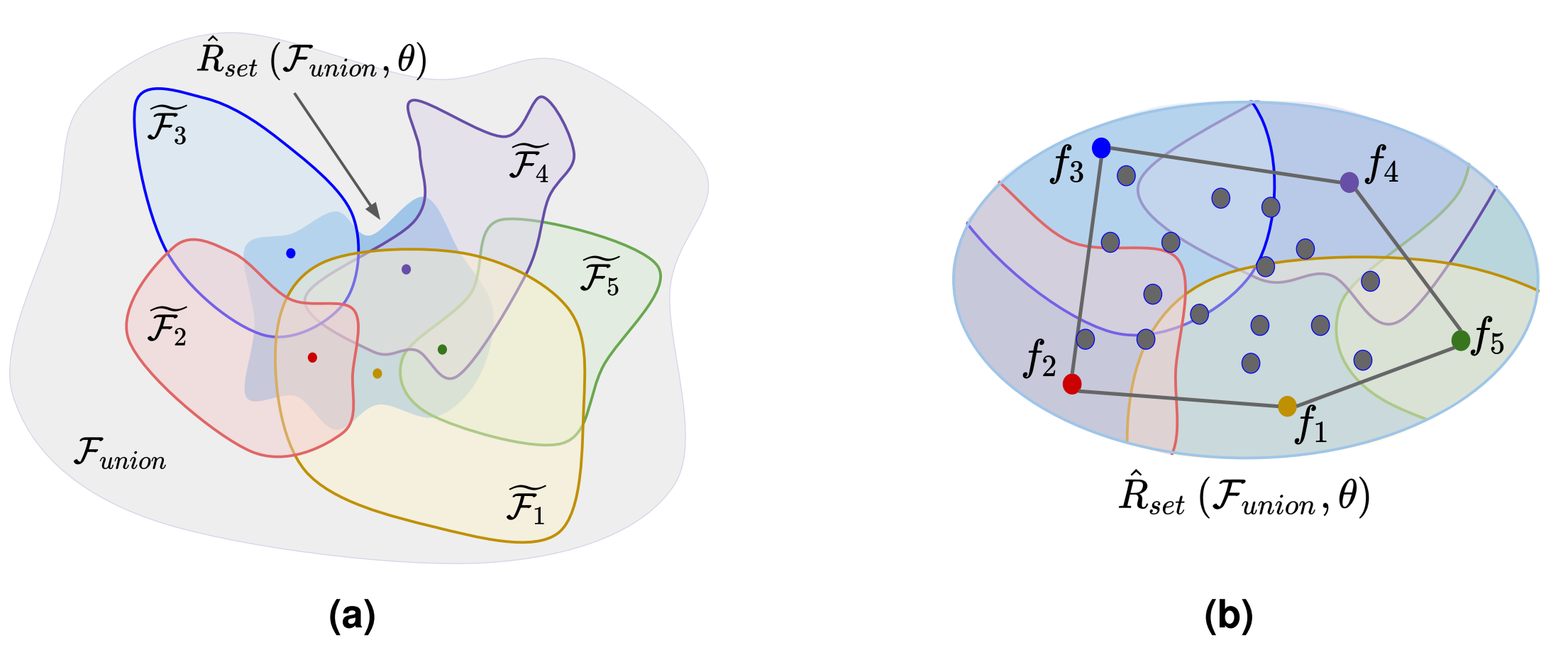

Rudin pushes back against the belief that complex black box models are necessarily more accurate, drawing on a formal learning theoretical argument. The intuition behind the argument can be understood using the depiction of model space in Figure 2, with model classes represented by $ \mathcal{\tilde{F}}_i $ and the overall model space by their union $\mathcal{F}_{union}$. In Figure 2a, each $\mathcal{\tilde{F}}_i $ ($ i=1,..,5 $) corresponds to a different model class, for example, neural networks or decision trees. In Figure 2b, the subset of model space spanned by each high-performing model $f_i$ is called the “Rashomon set” $ \mathcal{\hat{R}}_{set}$, given as a function of model space $\mathcal{F}_{union}$ and threshold $\theta$ for maximum loss performance (where the aim is to minimise loss). If you assume the Rashomon set is large, smooth, and convex (which are not unreasonable assumptions given the vastness of model space), then an interpretable model will exist somewhere within that set. There is a related model development heuristic called “Occam’s razor” which prioritises choosing simpler models in the assumption they do not overfit and generalise better. The Rashomon sets argument is more nuanced, applying Occam’s razor on multiple different model classes to get intuition for the underlying model space. Specifically, if model classes of differing complexity have diverse predictions but similar performance on a dataset, then interpretable models are likely to exist. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in a follow-up paper for tabular data [2], and is an active research area for raw data like images and text.

Rudin also addresses logistical issues surrounding IML and XAI. She notes that IML models can be hard to construct because of the resources required to gain domain expertise and identify required model constraints, as well as the computational difficulty of solving harder constrained models. However, Rudin’s counterargument is that analyst time and funding are less expensive than the cost of having a flawed model in a high-stakes situation, and so making models interpretable is worthwhile. Another concern is the XAI business model - namely, companies that profit from black box models are not responsible for the quality of individual predictions. Going back to the criminal recidivism prediction example, a deficiency in the model which produces a convoluted risk score could overestimate (or underestimate) a prisoner’s sentence, but the company that constructed the model would be unaffected. In fact, the model being a black box and proprietary is how the company profits because no individual predictions (correct or incorrect) can be linked back to specifics of their model. If instead we use an interpretable model, we would understand its predictions for individual datapoints since the internal mechanics of model reasoning are transparent to us. Although troubleshooting transparent models can produce fairer outcomes, this added responsibility is a significant business cost and so policymakers need to create other incentives for building interpretable models. For high-stakes decisions, stronger policies - like making it false advertising to sell black boxes if equally accurate interpretable models exist - can be used to shift the current business model.

Reflections on the Paper

Although Rudin advocates for IML, there are two unexplored topics in this paper - the exact definition of “high-stakes” and unsupervised learning with non-intuitive data - that, when taken together, provide a potential use case for XAI. Rudin implicitly defines “high-stakes decisions” through her examples of criminal recidivism prediction and medical diagnosis as decisions that significantly affect the quality of someone’s life. While these examples are clearly high-stakes, an explicit definition would clear up ambiguity around “potentially high-stakes” decisions, many of which appear in unsupervised life sciences problems.

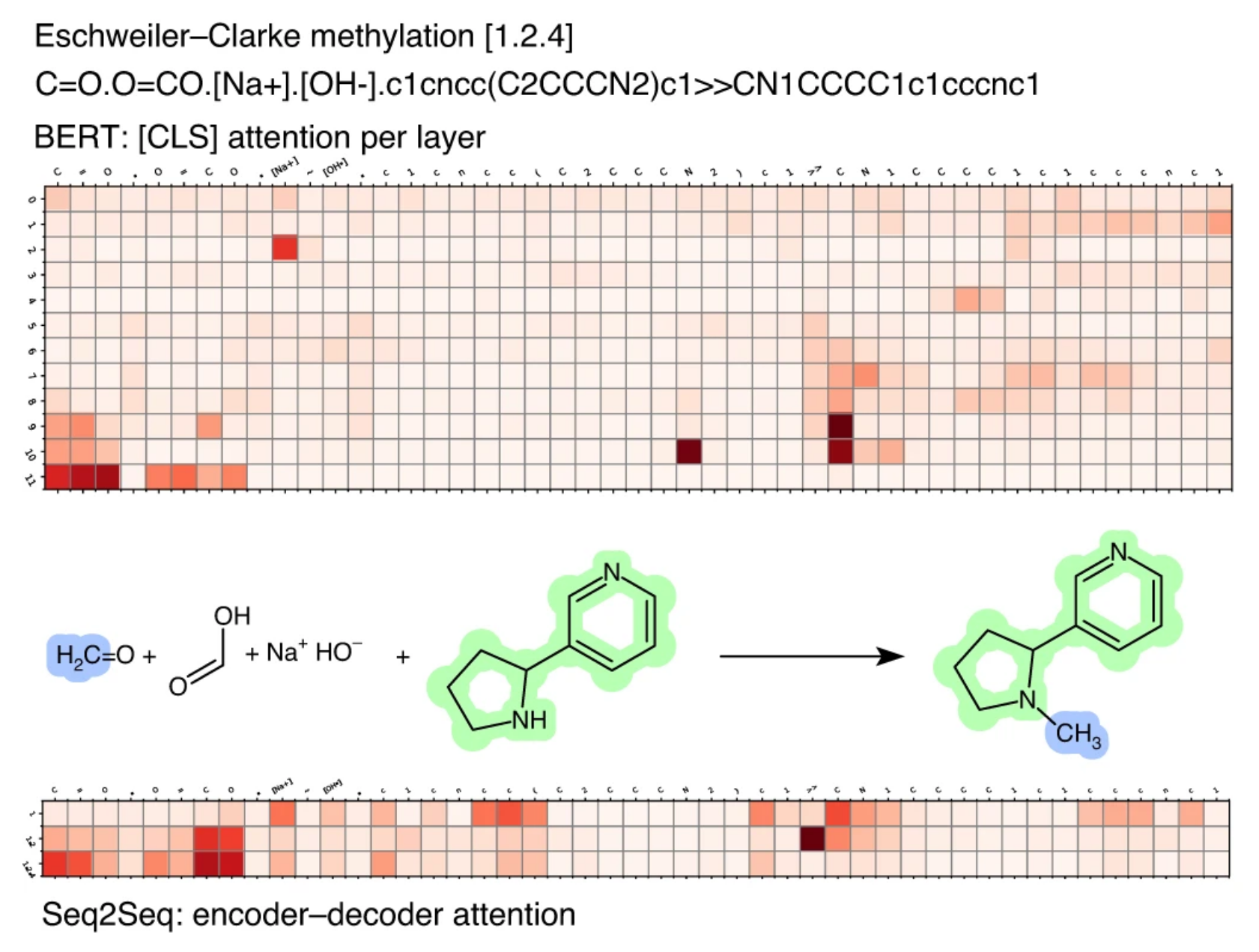

Figure 3.

Looking at the attention maps for chemical reaction tokens using two different models: the BERT transformer (top) and the seq-2-seq encoder-decoder (below) for methylation reaction. Darker elements correspond to reaction tokens with more attention. The authors found that larger attention weights were associated with the changes of a reaction. Adapted from [4].

For example, in computational chemistry, Schwaller and colleagues analysed text representations of chemical reactions using transformers and their corresponding explainable attention maps [3]. Taking the attention maps for each reaction as a unique reaction signature (as shown in Figure 3), they were able to map out chemical reaction space [4]. Guided by human scientists, this work was then used to identify viable synthesis routes in the lab for high-impact materials like drugs. In computational biology, Avsec et al. [5] predicted gene expression levels from text representations of genomic data, using attention maps to capture long-range receptive fields of genes. Similar to the Siberian husky example in Figure 1, these maps do not tell us how the relationship works between genes, but they do tell us that these relationships exist. And then using their biological knowledge, the authors were able to infer specific details of these gene regulation circuits. This kind of work could help identify mutations that cause rare disorders. For these unsupervised “potentially high-stakes” examples where we are presented with data in forms we understand (e.g. text) but with non-intuitive structure (e.g. chemical reaction structure, genomic structure), deep explainable methods guided by human expertise present a useful initial approach.

Figure 3.

Looking at the attention maps for chemical reaction tokens using two different models: the BERT transformer (top) and the seq-2-seq encoder-decoder (below) for methylation reaction. Darker elements correspond to reaction tokens with more attention. The authors found that larger attention weights were associated with the changes of a reaction. Adapted from [4].

For example, in computational chemistry, Schwaller and colleagues analysed text representations of chemical reactions using transformers and their corresponding explainable attention maps [3]. Taking the attention maps for each reaction as a unique reaction signature (as shown in Figure 3), they were able to map out chemical reaction space [4]. Guided by human scientists, this work was then used to identify viable synthesis routes in the lab for high-impact materials like drugs. In computational biology, Avsec et al. [5] predicted gene expression levels from text representations of genomic data, using attention maps to capture long-range receptive fields of genes. Similar to the Siberian husky example in Figure 1, these maps do not tell us how the relationship works between genes, but they do tell us that these relationships exist. And then using their biological knowledge, the authors were able to infer specific details of these gene regulation circuits. This kind of work could help identify mutations that cause rare disorders. For these unsupervised “potentially high-stakes” examples where we are presented with data in forms we understand (e.g. text) but with non-intuitive structure (e.g. chemical reaction structure, genomic structure), deep explainable methods guided by human expertise present a useful initial approach.

In fact, work of this kind broadens the toolkit of the first stage of model development - exploratory data analysis (EDA). Deep learning’s black box nature limits its use in the final model development stage, but its effectiveness on a wide range of tasks makes it well-suited to initial exploration. As part of my PhD programme, I presented a summary of Rudin’s paper to the rest of the cohort. During the presentation, an audience member asked “whether this paper indicates the end of black boxes and deep learning (DL)?” - my answer was a resounding no. I believe it will evolve into two things: firstly, the aforementioned integration with the EDA process, and secondly, into hybrid models of DL and IML (a.k.a. interpretable neural networks), which constrain the unbounded expressivity of neural networks (NNs) with domain-specific knowledge. Some examples of this latter work include neural additive models [6] which combine NNs with the interpretable model class of generalised additive models, conceptually-disentangled NNs which revolve around assigning meaningful concepts to the network’s neurons to understand the model’s reasoning [7, 8] Note that the second reference is from Rudin’s lab. They cover more examples of disentangled neural networks in Chapters 5 and 6 of their recent review paper looking at major challenges for interpretable machine learning [17]. , and broader model classes that combine NNs with mechanistic differential equation systems such as neural ordinary differential equations [9] and physics-informed NNs [10].

And this leads onto another recurring question from my cohort’s feedback - “as students focussed on AI applied to healthcare (i.e. a high-stakes field), how can we get involved in IML?” Although it may seem counterintuitive, my working answer is do not focus completely on ML/DL methods and make sure to learn the classical interpretable models of your field. ML’s widespread interest has led to highly accessible frameworks for beginners (e.g. $\texttt{scikit-learn}$, $\texttt{PyTorch}$, $\texttt{HuggingFace}$) so if you believe that it will evolve into hybrid models, dedicate more time to learning your domain thoroughly to find fruitful intersection areas. Specifically, you can figure out how DL’s main strength - expressivity - can expand the classical model search space for your domain in a reasonable way. Answering the question more practically for day-to-day work, we should aim to build models in a manner consistent with the Rashomon sets argument. In other words, set a threshold for acceptable performance early, and only use deep methods after trying and incrementally improving multiple interpretable model classes to limited success.

Our final remark on the paper considers complex explanations. As humans, our decision-making processes can be complex [11], but we often give a basic explanation from which there could be many, similar to how the racist explanation for criminal recidivism example was an oversimplification from a subset of feature space. The question then arises, ``how could we deal with many complex explanations?’’ And the answer to this is by treating interpretability as a software engineering problem, not just a data science/model building one. To illustrate this need better, let’s look at the complexity of two systems: a massive NN with billions of parameters and the original Linux kernel which, when compiled, has around 130 million parameters [12]. Taking complexity as the number of variable parameters in a system (an imprecise but not-inaccurate metric), the NN is more complex than the kernel. However, we can understand the Linux kernel because interpretability was treated as a software engineering task and APIs were built that we can reason about. Put another way, we may be able to break down complex computations into simpler interpretable components. Using software engineering principles to understand black boxes is a nascent research field, but neural programming languages for recurrent NNs [13] and attention [14] alongside reverse engineering convolutional NNs [15] and transformers [16] have been important first steps towards identifying modular components of NN mechanics.

Conclusion

In this paper, Prof. Cynthia Rudin makes an important distinction between interpretable and explainable machine learning, and I agree with her main message that high-stakes problems necessitate interpretable models. However, since this paper being published in 2019, transformers and their attention maps have shown success over a range of high-dimensional data tasks, which has led me to think that Rudin’s original hypothesis for explainability in high-stakes decisions can be updated. With a more nuanced definition of high-stakes decisions, there is space for explainable models early in the model development process, particularly for unsupervised work on non-intuitive data. And looking further ahead, recent work into understanding transformer mechanisms could be the key to making previously-explainable methods interpretable and creating interpretable neural network frameworks which are accessible to practitioners from a variety of fields. So, is this the end of deep learning as we know it? At the very least, I think it’s the start of the end. Questions remain over optimal policies for incentivising interpretable model building but given that high-stakes data science problems are prevalent across academia, industry, and government, the future looks promising for formal interdisciplinary notions of interpretability. And hopefully at some point in the future, the thought of using a completely unexplained black box will seem like a distant memory. In the meantime, us applied scientists can work towards closing the interpretability gap on deep learning and help realise its potential for scientific discovery.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UKRI CDT in AI for Healthcare http://ai4health.io (Grant No. EP/S023283/1) and AstraZeneca. Special thanks to other members of the CDT for their thoughtful questions, and Ahmed Fetit and Joram M. Posma for checking over drafts of this.

Bibliography

[1] C. Rudin, “Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead,” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 206–215, 2019.

[2] L. Semenova, C. Rudin, and R. Parr, “A study in rashomon curves and volumes: A new perspective on generalization and model simplicity in machine learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.01755, 2019.

[3] P. Schwaller, T. Laino, T. Gaudin, P. Bolgar, C. A. Hunter, C. Bekas, and A. A. Lee,

“Molecular transformer: a model for uncertainty-calibrated chemical reaction prediction,” ACS Central Science, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 1572–1583, 2019.

[4] P. Schwaller, D. Probst, A. C. Vaucher, V. H. Nair, D. Kreutter, T. Laino, and J.L. Reymond, “Mapping the space of chemical reactions using attention-based neural networks,” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 144–152, 2021.

[5] Z. Avsec, V. Agarwal, D. Visentin, J. R. Ledsam, A. Grabska-Barwinska, K. R. Taylor,

Y. Assael, J. Jumper, P. Kohli, and D. R. Kelley, “Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions,” Nature Methods, vol. 18, pp. 1196–1203, 2021.

[6] R. Agarwal, N. Frosst, X. Zhang, R. Caruana, and G. E. Hinton, “Neural additive models: Interpretable machine learning with neural nets,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021.

[7] P. W. Koh, T. Nguyen, Y. S. Tang, S. Mussmann, E. Pierson, B. Kim, and P. Liang, “Concept bottleneck models,” International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 37, pp. 5338–5348, 2020.

[8] Z. Chen, Y. Bei, and C. Rudin, “Concept whitening for interpretable image recognition,”

Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 772–782, 2020.

[9] R. T. Chen, Y. Rubanova, J. Bettencourt, and D. Duvenaud, “Neural ordinary differential equations,” in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 32, pp. 6572–6583, 2018.

[10] M. Raissi, P. Perdikaris, and G. E. Karniadakis, “Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations,” Journal of Computational Physics, vol. 378, pp. 686–707, 2019.

[11] V. Pande, “Why we shouldn’t fear the ‘black box’ of ai (in healthcare and everywhere).” https://future.a16z.com/podcasts/black-box-ai-healthcare/, Posted 28/02/2018. Accessed: 16/01/2022.

[12] C. Olah (@ch402), “Tweet on complex neural network explanations by main author of

papers on reverse engineering cnns and transformers.”

https://twitter.com/ch402/status/1454998974935416837, Posted 01/11/2021. Accessed: 13/01/2022.

[13] J.Z. Kim, and D.S. Bassett, “A neural programming language for the reservoir computer,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.05032, 2022. Accessed: 27/08/2022.

[14] G. Weiss, Y. Goldberg, and E. Yahav, “Thinking like transformers,” International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 38, pp. 11080–11090, 2021.

[15] N. Cammarata, S. Carter, G. Goh, C. Olah, M. Petrov, L. Schubert, C. Voss, B. Egan, and S. K. Lim, “Thread: circuits,” Distill, 2020. https://distill.pub/2020/circuits.

[16] N. Elhage, N. Nanda, C. Olsson, T. Henighan, N. Joseph, B. Mann, A. Askell, Y. Bai, A. Chen, T. Conerly, N. DasSarma, D. Drain, D. Ganguli, Z. Hatfield-Dodds, D. Hernandez, A. Jones, J. Kernion, L. Lovitt, K. Ndousse, D. Amodei, T. Brown, J. Clark, J. Kaplan, S. McCandlish, and C. Olah, “A mathematical framework for transformer circuits,” Transformer Circuits Thread, 2021. https://transformer-circuits.pub/2021/framework/index.html.

[17] C. Rudin, C. Chen, Z. Chen, H. Huang, L. Semenova, and C. Zhong, “Interpretable machine learning: Fundamental principles and 10 grand challenges,” Statistics Surveys, vol. 16, pp. 1-85, 2022.

This post can be cited as:

@article{vijayaraghavan2022rudin,

title = "Reflections on Rudin's interpretability classic",

author = "Vijayaraghavan, Avish",

journal = "avishvj.github.io",

year = "2022",

url = "https://avishvj.github.io/posts/rudin/"

}