Avish Vijayaraghavan

How we wrote a big review paper on multimodal AI

A research retrospective on a two-year-long 50-person collaboration

Contents

Introduction

We recently published a big collaborative perspective paper in Nature Machine Intelligence on multimodal AI across six domains - healthcare, finance, science, engineering, social sciences, and sustainability - with three case studies: self-driving cars, pandemic response, and climate change adaptation. The project brought together roughly 50 academics and spanned two years from the initial meeting to publication. I served as a healthcare co-lead, and the experience taught me a little bit about large-scale collaborative research. I wanted to detail the process of deciding what to write about, how everyone contributed, and some learnings. I’ll start with a timeline and then go into reflections.

Timeline

(2023 Q4) Initial steps: scoping, reading, notetaking

The first challenge in any review paper is defining scope, and we chose to tackle arguably the broadest possible scope for a machine learning paper, perhaps any research paper, given that ML serves as a tool across any domain where data can be collected. Our only constraint was prioritising data modalities beyond the dominant vision and language paradigms. This initial scope of multimodal AI beyond vision and language was proposed by the main paper leads, Haiping Lu and Xianyuan Liu from Sheffield University. Naturally, the breadth added logistical challenges: coordinating 50 contributors, managing sporadic but intense bursts of contributions over two years, and combining a variety of perspectives into a short coherent narrative.

The project began with an in-person meeting in November at the Turing Institute, organised by Haiping and Xianyuan. This was an initial session to get everyone in the room together where people did short pitches of their multimodal work and then there were breakout rooms for each domain where members brainstormed ideas and carved out their sections - healthcare people took healthcare, climate folks took environmental sustainability, and so on. The goal was straightforward: write about multimodal AI in your domain.

Out of this brainstorming session, the healthcare domain I was part of emerged with a document of important themes for us to incorporate. We looked at different data types and datasets - their availability, collection costs, and limitations like small sample sizes with high dimensionality and population bias. For different data types, we noted specific challenges - for example, clinical text has issues around medical jargon and patient-identifiable information. The data types were broad: structured, unstructured, biosignals, omics, trial data, and so on. Getting multimodal analysis techniques together involved identifying previous reviews covering approaches like joint representations, fusion, and co-learning, alongside unifying frameworks like graph machine learning and multimodal transformers.

Then it was on to applications: diagnosis, prognosis, public health, hypothesis generation. We focused on finding areas where being multimodal makes a difference - diseases that are not monocausal, risk prediction needing wider signals for robustness. A previous paper on multimodal biomedical AI covered applications like clinical trials, digital twins, and pandemic surveillance, which meant our value-add had to build on this and tie into broader themes from other domains. There was also the wider issue of translation: how does the shift from unimodal to multimodal health AI change evaluation, clinical and patient interactions, and general challenges around infrastructure (additional storage and costs) and privacy concerns/information leakage (via multiple modalities).

From the beginning, we knew that in-person meetings wouldn’t be practical since the team was mostly spread out across England (alongside a few researchers in Scotland, Norway, and China), but a check-in was planned later on once the paper had started to take some shape. The leads tried Google Spaces for regular communications and weekly drop-ins early on but it was hard to get into a good cadence. Asynchronous collaboration via email with bimonthly-ish meetings near deadlines ended up being a practical alternative. They also created an overview document which include reminders of the objective, links to relevant files, the work plan leading into the next phases (submission was originally planned for April 2024!), and other FAQs. We also settled on a target audience: mostly academia (no specific niche) with some ways to bridge to industry.

What followed was a lot of paper reading. I’ve had intensive reading periods in my PhD but it’s usually focussed on niche fields with the aim of coding up ideas and testing them with appropriate experiments to push a narrow area forward. This perspective was about neither of those things, it was about building a map of the field via papers. A huge dot connecting exercise, akin to building a map of the world via information on each city. Trying to cover reading across the entire field of healthcare was hard but two useful heuristics I found were: (1) finding review papers for AI applied to big disease classes (e.g. neurodegenerative diseases, cancer) and (2) looking for reviews of relevant modalities (e.g. wearables, graphs) where they’ll mention multimodal learning in the final section as an ambition for the field with some potential health-focussed papers (e.g. “it would be good to combine wearables with images for a complete picture of your health”). That’s around the time I realised that taking a scope as broad as we had required really understanding existing reviews deeply. We were a review of reviews - a meta-review - with additional individual papers to fill in gaps.

Everyone worked independently on their sections, contributing directly to the document and marking their work with comments containing their names. The initial phase involved all that reading, then drafting paragraphs combining common methods/ideas/themes, adding relevant references, and including figures where appropriate.

November and early December were focused on direct contributions. By mid December, we had a full team meeting to review progress and discuss the bigger picture: how do we turn this collection of domain-specific pieces into a coherent narrative? That was the question we let marinate as we went into the Christmas holidays.

(2024 Q1) The co-lead phase: finding common threads and our value-add

We reconvened in early January with a clearer sense of direction. I had contributed a fair bit to the doc and was invited to join as a healthcare co-lead with my focus being clinical deployment. I spent a lot of time updating content on ophthalmology (eye-related medicine) and cardiovascular applications, which were less explored than areas like cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and COVID-19. My aim was to hit as many “big” areas of healthcare as possible to identify if themes cropped up across them. One challenge was existing work in certain areas wasn’t as specific as we’d hoped, which became an opportunity for us to identify where our review could add unique value. There was an initial structure laid out by the main leads and as we went along, we asked ourselves whether our work fit into that or whether we needed to change up the structure slightly.

We were doing this all in Overleaf and I distinctly remember a draft spanning 50+ pages that had to be refined. At the time, part of me was hoping we could shove the whole thing out and cover everything in depth. In hindsight though, that draft was far too messy and unstructured. It was the subsequent writing, refining, and condensing that really gave us a clear enough story for the paper to work. I think this is also why it helps to know your audience - we took a broad scope and wanted a broad audience. It could be great to have a hyper-detailed document on all six domains, but how many people would actually read that as well? If you’re still reading this blog post, you’re probably in a minority of 2% who clicked on this post (of the 1-5% who saw the post on socials and clicked the link). And this blog post is far less formal or mentally-demanding than a research paper.

This is where things started to crystallise properly. We were identifying common themes across sections using a Google Sheets form sent to all collaborators. What problems kept showing up? What made multimodal AI necessary rather than just nice-to-have? And then on integration: what ideas spanned multiple domains? What were the high-priority points for each section?

Early-to-mid-February is when the ideas became more concrete, shifting to three use cases: COVID, Cars, and Climate (3Cs, from micro to macro scales), which could act as mini-stories for combinations of the domains to make the most out of limited space. For balanced content, each use case would be covered by two domains: the COVID-19 pandemic by healthcare and social sciences; car manufacturing by engineering and science; and climate change by finance and sustainability. This was the spine of the paper - showing problems where computer vision or NLP aren’t enough, and where we needed to cut across more than one domain to properly solve the problem.

We then added a file that served as a scratchpad for rough ideas for each domain, alongside the initial draft that everyone had contributed to.

By early/mid-February, we had our framework sorted. Each domain section would answer five key questions:

- Current state: Where is multimodal AI in this domain right now?

- Importance: Why does this domain need multimodal AI?

- Beyond vision and language: Why do we need modalities beyond the usual suspects?

- Beyond this domain: What other fields should we be learning from?

- Actions: How do we move forward as a community?

There were four healthcare co-leads. We met and started identifying common threads from papers, then grouped these into four broader themes - each with its own co-lead responsible for merging individual contributions into paragraphs aligned with the five questions. The themes were: opportunities & techniques for multimodal learning beyond image and text; variation across specialties and disciplines; real-world impact via evaluation and clinical pathway integration; and the technical side of multimodal learning. The latter ended up becoming part of a general precursor section on multimodal learning across all domains.

I took the “real-world impact” section which pushed me outside my domain to think about all the ways we actually get models into the clinic and why that’s hard. On a personal level, it was very useful for my PhD. My main focus is making models so I hadn’t thought as much about the actual data collection (sequencing platforms) and turnaround times, the instrument reliability, the health economics side, and the integration into doctor workflows. My core finding was that the current state of health AI was still research-focussed and many models were failing at the regulatory hurdles. Ultimately, the intention for translation was there, we just needed to take more inspiration from areas that were clinically mature like medical imaging.

Fitting this into the five-question framework meant: highlighting how we can combine well-known modalities for personalised medicine (current state and importance); noting validation challenges like medical AI devices often being evaluated at only a small number of sites, alongside data quality and quantity issues (current state); emphasising the wealth of biological data beyond vision and language (beyond vision and language); connecting to climate change as the WHO-identified biggest problem facing health (beyond this domain); and proposing specific actions around developing multimodal datasets that reflect patient pathway complexities, data standardisation, refining human-AI collaboration, expanding trusted research environments for privacy-preserved data use, and more work into understudied areas like multimorbidity and rare diseases.

We ended the quarter with another event for the wider UK multimodal AI community where we presented some of these more structured ideas.

(2024 Q2-Q4) The main lead phase: building a coherent story

April to June was when the main leads for each domain took over refining everything. This phase required synthesising contributions from the co-leads (2-5 people per domain) to create the grand narrative for the paper. At some point in May, the leads asked us to gather 5-10 representative multimodal databases from each domain so that we could create a table showcasing key data modalities and give a quick “in” to researchers exploring the area who wanted to build models.

Most existing papers I’d reviewed were unimodal and discussed limitations around robust models - hence we made a point to mention how multiple modalities could enhance that robustness. The leads added tables, diagrams, and figures to strengthen the visual side of the paper’s story. One important subtle change was that car manufacturing had shifted to a focus on self-driving cars to bridge science and engineering better.

By late June we had a first draft. We were still facing the lurking shadow of word count: Nature Machine Intelligence wanted around 4,500 words and we were sitting at 9,000.

All collaborators reviewed it, identifying content that wasn’t unique to multimodal learning or its specific domain and suggesting cuts. Even with aggressive editing, it was a struggle to get below 8,000 words. Some sections had developed such strong narrative flow that cutting them felt counterproductive. As a brief aside on comms, one thing I noticed was that if you need feedback from a big team, setting a 2-3 week period is sufficient to get diverse enough responses.

Then, in August, the leads restricted access to the Overleaf document to finalise the submission version. Communication became more limited as final manuscript preparations took place under the lead authors. In late November, we received a penultimate version that was pretty much within the word count, with one last opportunity to flag any significant issues.

(2025 Q1-Q2) Final comments and submission

In late February, we received the final version. Final comments were given, authorship and acknowledgements were locked in. We posted a preprint on arXiv and submitted to Nature Machine Intelligence in late March - though we needed to keep the submission quiet during the review process.

(2025 Q3-Q4) Useful suggestions from reviewers and acceptance!

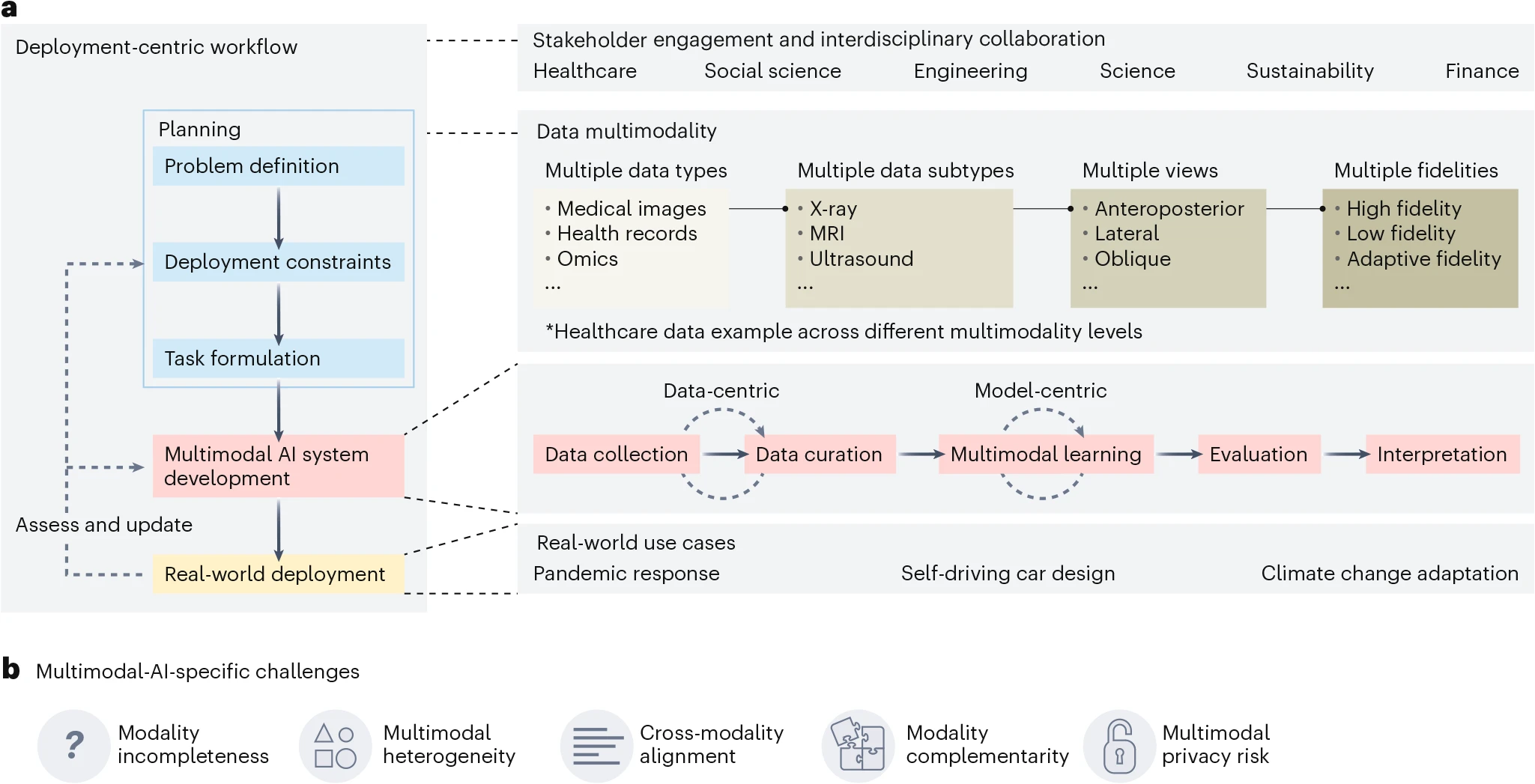

Mid-June brought the reviews. The feedback raised important points: the reviewers wanted more emphasis on LLMs and generative AI (we hadn’t discussed them explicitly enough), stronger interdisciplinary framing (which was tough to modify as we thought we had done this via the three use cases!), and better inclusion of domain experts and policymakers. They also highlighted a supplementary figure we’d included that showed how little work had been done on multimodal AI beyond vision and language. We moved it into the main text, as it made a stronger visual case for the paper’s core argument.

Early July was revision mode. We organised things by having a document of the reviews where we could all comment and provide feedback. Haiping and Xianyuan then went and made as many changes as they could without disrupting the paper’s flow. They added discussion on problem constraints, the community element of the problem (all the different stakeholders required in coordination), and the uniqueness of multimodal deployment challenges. Addressing the LLM gap required us to reframe our thinking a bit - it made sense we had ignored it given our focus beyond vision and language, but beyond doesn’t necessarily mean excluding. Viewing language models as an interface for other models (e.g. chatbots), we added how multimodal foundation models with text as one of the modalities could be impactful for improving accessibility. A graph foundation model is useful to anyone who understands graphs, a graph-language foundation model is useful to anyone in the field. All-in-all, a useful and fairly pleasant reviewing experience!

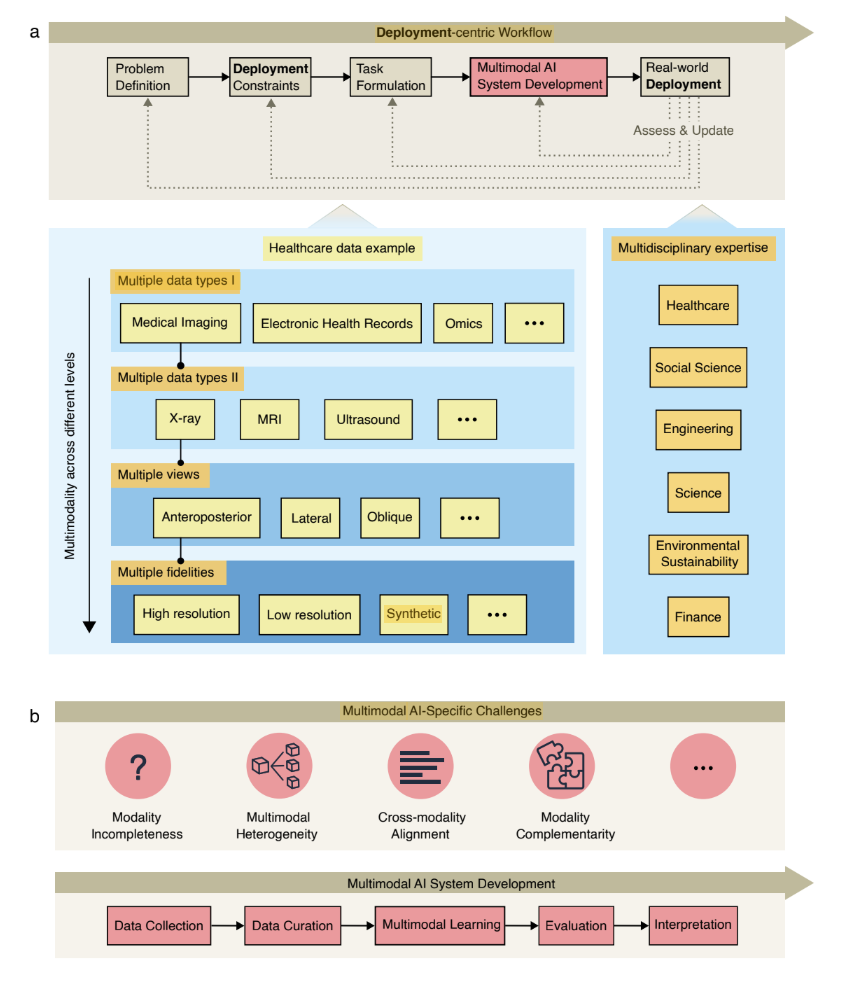

You can also see how our diagram style changed to fit Nature’s:

We sent back the responses in July. By mid-August, we received the acceptance and the paper was published in late October.

Reflections

The research process. It was quite meta but also quite natural: much of what we discussed during the project - be it clarifications, paper direction, how to organise ideas - was the research work. Figuring out how to combine everyone’s perspectives required far more thought and feedback than any individual contribution, but that integration was the actual value of the review. To make that integration efficient, it followed a hierarchy. Opinions on structure were sourced from everyone but the main leads made the final decision and this was given more structure by the domain co-leads. I was one of the four healthcare co-leads focused on real-world deployment, so I went through all the individual healthcare contributions, picked the bits relevant to my theme, then arranged them into a mini-story that fit the structure defined by the main paper leads. Each co-lead for each domain would’ve done something similar.

What worked well. The organisational structure was excellent from the start and all credit to the main paper leads and main co-lead for each domain. From my experience as a PhD student working on narrower projects in a fairly niche university division (Systems Medicine at Imperial), you rarely get exposed to huge projects like this and I was impressed by how smoothly it went, all things considered. Once we established those five key questions for each domain section, the paper’s framework became a lot clearer. The cross-domain use cases - COVID-19, self-driving cars, and climate change - gave us strong narrative threads that showed how multimodal AI could cut across traditional problem boundaries. Having the basic hierarchy of main leads > co-leads per domain > individual contributors made the combination steps much simpler. In the end, collaborating between 50 people came down to five things: a clear high-level objective, minimal hierarchy (main project leads + 2-4 co-leads per team), firm deadlines (loosely held), organised folders/files people could comment on, and regular emails.

What could be improved. Honestly, not much - there are only two things that pop out. The first is that we had a huge draft initially with all types of research and it felt like a shame to compress it down to 4500 words for the journal. But everything is a trade-off - the word limit forced a tighter story, which made it more accessible and led us to prioritise the three real-world use cases that tied the domains together nicely. Maybe an in-between solution could be the 9000 word version on arXiv? The other thing is that certain domains had more specialists than others - healthcare, science, and engineering had more specialists than sustainability, finance, and social science. It didn’t seem to affect the quality of each section but what that meant in practice was bigger responsibility on the (fewer) co-leads of those domains. Maybe a subsequent call for researchers within those domains would’ve helped (and I imagine they did this informally for specific areas where expertise was lacking).

Looking forward. The organisers have used the momentum from this paper to create the UK Open Multimodal AI Network (UKOMAIN), a community that hosts workshops to document the UK’s open source multimodal research and has recently received a large EPSRC grant of £1.8M to tackle key engineering research challenges. That’s taken what could have been a one-off publication and turned it into an ongoing effort to advance the field and help seed future collaborations. It’s really cool how it happened so organically from that initial November ‘23 meeting, into other events in March ‘24, June ‘24, etc. That’s one big recommendation I’d give to anyone who manages to get 50 people to collaborate on a project - keep those connections going in whatever way you can because it doesn’t happen often!

Conclusion

I don’t think there’s ever a wrong time to write a review paper. You can write one early in your career as you survey the field, you can write one late in your career as you give opinions on better directions, you can come at it from a different field altogether, you can take any scope as long as you give it some sort of structure. We took one of the broadest scopes possible for a paper (ML, the most general tool for data, applied to six broad domains, only limited by data modalities and journal word count) and, accordingly, had researchers from the full spectrum of backgrounds and experience levels.

For anyone considering a similar large-scale collaborative review, my main takeaway is this: solid organisational structure from the beginning makes an enormous difference. The organisers of this project did excellent work managing roughly 50 academics across multiple domains, and their planning - from the initial division of labour to the phased integration process - was key to the paper’s success. It’s not easy to synthesise such broad expertise but having an open dialogue and communication channels with semi-regular check-ins helped a lot, and generally being open-minded about the direction of the paper helped too. There was no bias, it was just “let people read and we’ll figure it out as we go along” and that’s why we ended up with something that is hopefully more than just a snapshot of the field, but offers principles that will apply to multimodal AI going forward.