Avish Vijayaraghavan

Stuck between two black boxes

Drug discovery is not a tech problem yet

Introduction

When I was thinking of getting into biotech investing, I read a post on Reddit which said “don’t touch it with a bargepole”. After a month-long stint consulting with a biotech investment team, I reckon more accurate advice would be “don’t touch it unless you know enough biology to stomach the uncertainty”. I was working with the team’s head, Emil, and we focussed on public pharma companies who are using AI for drug discovery, the field I’ll refer to as pharmatech. Investing in pharma basically requires replicating someone’s research from your computer: you take the snippets of information you get from a company about their drug mechanisms and development process, figure out if the literature supports both, and predict if their drug will get to market. Both you and the scientists have access to the same literature but the major difference is they also have proprietary data and technology. The whole thing is riddled with uncertainty, from the asymmetry of information, to whether the technology works like the company claims, or even if the data is representative of the actual disease biology. Over the course of the month, I grew more and more skeptical of drug discovery companies using AI and I want to explain why I think many of these companies are focussing on the wrong problems.

AI for drug discovery: discovery or optimisation?

The first thing Emil and I did before starting was create a list of publicly-traded companies which we refined to a few for a deep dive. We wanted to centre the analysis around AI platforms used for drug discovery so I spent the first week going over drug discovery reviews to derive better criteria for the platforms. We settled on some simpler things first: existence of proprietary data, efficacy data, and toxicology data. I searched through annual reports for any important info and found out companies in this (somewhat?) niche space can still have surprisingly different missions. BenevolentAI takes on a similar mission to traditional pharma companies but emphasises their use of AI tools^. ^And while editing this post, they’ve had poor clinical trial results and made plans to fire a lot of staff… Roivant, on the other hand, is almost like a biotech index fund - it consists of multiple sub-companies (called “Vants”) which target different aspects of healthcare e.g. Dermavant for skincare, Proteovant for protein-based drugs, etc.. And then you have companies like Absci who seem like they’re gearing up to be generative drug discovery-as-a-service for antibody-based drugs - think ChatGPT but your prompt is an antibody instead of text.

What we found pretty early on is that there’s such a small amount of information available on these companies. Occasionally, they’ll publish papers but they restrict important information - this paper by Absci shows some very interesting results and gives access to some output data for the research community, but there’s little info on the model being used. We could have analysed these companies like standard pharma companies by looking at their drug pipeline but the point was to figure out if AI is really helping the companies speed up the drug development process. In this great paper by Andreas Bender, he lays out the challenges that AI in drug discovery faces. And the overarching message I got^ ^And that I can self-verify from countless hours spent wondering why my models aren’t working on patient data. is that life sciences data is very context-dependent. It isn’t as clean as text or images which are the modalities used in well-known models like GPT and Stable Diffusion. Different assays are used, these are hard to standardise, and it’s not clear exactly what different data modalities are telling us, especially when they aren’t collected over time.

Another major concern is that AI models are just glorified averaging machines - they don’t help you extrapolate beyond anything in your training data^ ^Although maybe this is changing… and so all you’ll be doing is interpolating between known drugs. Derek Lowe explains this scenario clearly here, a pharmatech company like Exscientia may just be exploring well-known areas of drug space that haven’t been patented rather than actually discovering new drugs. That’s not necessarily a criticism - if it works, it works, and Exscientia seem to be doing alright, but it’s more drug optimisation than it is drug discovery. Based on this idea, Emil suggested inverting the process. Rather than judging the quality of AI discovery platforms based on the platform itself, look at drugs from pharmatech companies, relate them to the literature, and judge a platform’s quality on whether it’s discovering new areas of disease and drug space or simply optimising within existing areas. This was a more efficient way to filter companies… and we said no to most of them!

Drugs and AI, two black boxes

Pharma is different to tech in many ways. Tech companies have much shorter timeframes, are refined through rapid and constant iteration on customer feedback (i.e. agile), and their research results are not made publicly available immediately after a “development cycle” like drugs. Pharma is a scientific industry with public results - drugs are tested under lengthy phases of clinical trials (i.e. not agile) and regardless of a good or bad result, the results are published for everyone to see. There is, however, one clear parallel between both industries that became clearer after the tech pivot to AI post-ChatGPT: they both rely on black boxes. And I think this is where the issues are coming from - this is the thing that makes it easier to think it’s discovery rather than optimisation.

A “black box” is the name given to any system that takes an input and gives you an output without telling you explicitly how the input became the output. This is the common thread between tech and pharma: lots of AI models are black boxes and lots of drugs are black boxes. This isn’t a new idea - Hugh Harvey has been talking about the similarities between algorithms and drugs for a while but the huge AI models of the past year have emphasised it. These models reach a level of complexity and scale that makes it hard to determine their inner mechanisms, and biology is so unbelievably varied between patients that it becomes hard to say with certainty what drugs are doing across a population. While this can seem worrying initially, both products get stress-tested to work sufficiently well, be that GPT-4 performing well across a range of tasks or general anaesthetic showing its utility for all kinds of surgery. Pharmatech companies have combined the two products with the central thesis that technology can drastically decrease the time needed to develop a drug. But it’s not clear if the technology is targetting the bits of the pipeline that really matter or, maybe more cynically, just the bits that seem cool.

From what I’m aware of, large AI models are used predominantly for hypothesis identification,^ ^Which is figuring out which disease mechanism-drug combos could be useful for further study usually over huge knowledge graphs combining information from biomedical literature, biological databases online, and wet lab results. But the problem of hypothesis identification seems less important compared to establishing a clear stakeholder network in a disease area, recruiting representative patient cohorts and careful trial design.^ ^The disclaimer is that maybe they are doing these things. There are far far more experienced people working in these companies than me so I’m sure these things have been discussed. Why they aren’t elaborated on publicly is unclear to me - maybe those problems are harder than I’m thinking? In other words, maximising conditions to create data with high signal-to-noise ratio. Creating and learning over a large multi-modal knowledge graph is already challenging, but doing it with varied biological sources across time, geography, and assay choice, as well as including alternate modalities like literature and pathways will require extensive QC to be reliable. Extensive to the point that that the QC would become your real proprietary technology!

Take one look at the drug pipelines of these companies and they all seem very broad. As a business strategy, sure, it makes sense to hedge your bets across multiple drugs. But that doesn’t seem like a good scientific strategy to me. Getting one drug to market is super hard in itself, and so even with lots of money, aren’t you spreading yourself thin trying to work on multiple drugs across different diseases?^ ^A counter to this point may be Roivant: they took this idea to the extreme with their multi-company business model and have a very impressive pipeline. But then it’s not clear if the sub-companies even work with each other… so who knows? The Bender paper also mentions that biology is driven by understanding more than unbiased data-driven science. The understanding is what allows you to filter non-useful hypotheses and generate better ones to drive further data collection. If your development process involves multiple black boxes, understanding becomes harder. That can be a good when talking to investors - “hey, look at this cool advanced tech that is so powerful even we don’t understand it” - but it loses the specificity required to actually find a drug.

Conclusion

I try my best to avoid conversations about AI models taking over the world and big pharma conspiracy theories because they take one kernel of truth (e.g. AI models are (relatively) powerful, pharma companies are driven (partially) by profit) and then extrapolate them beyond silliness. But the combination of proprietary aspects on both sides seems like it plays into this hype in the wrong way. Let me be clear. It’s not that I think companies would engage in any malpractice. It’s that the asymmetry of information increases at least two-fold with two black boxes: proprietary AI models and proprietary drugs. This isn’t a discussion for or against capitalism - proprietary technology is important and is what allows these companies to get funding and grow, I’m not disputing that. But drug discovery is a multi-stage process and using such complex tech for siloed parts of the overall problem does not feel useful. It seems more like a marketing tool than something functional to the company’s mission.

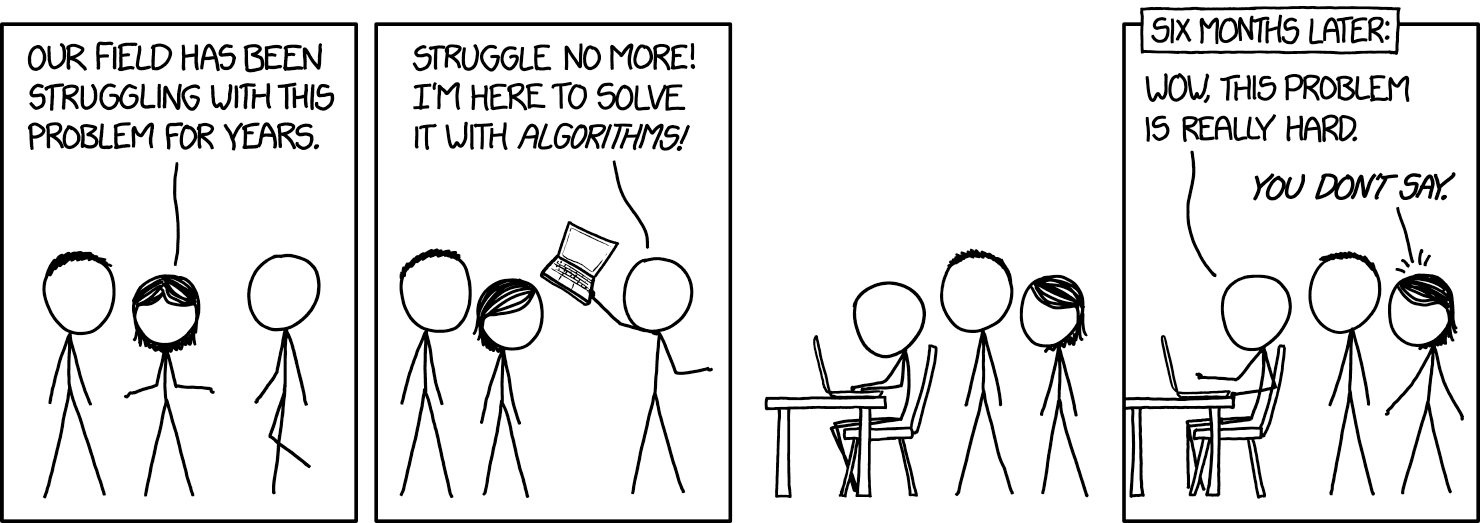

The social problem of drug discovery still seems like the biggest obstacle. I don’t know what the solution is, but I feel the public need to be more involved in this process - be it at the data level, understanding level, whatever. That can take on lots of strains: smarter patient recruitment via patient selection software, sharing healthcare ideas via community-based social networks, even crowdsourcing solutions via discovery science. The results from these things may be more modest on the surface (e.g. getting drug development from 10y to 9y) and the regulation behind these things may be complex too. But I think they will lead to greater and more consistent improvements over time than current pharmatech claims. Technology can help, I certainly believe it can, but you can’t sidestep or automate away the hard issues of understanding science and collecting high quality data. Once the data and people problems are improved, then the tech can take centre stage. Until then, it’s not quite “garbage in, garbage out” but it’s not ideal. To slightly paraphrase the conclusion from Harvey’s paper: “Neither drugs nor AI deliver safe and effective healthcare, people and systems do”. And if we aren’t focussed on the whole system of drug discovery, then we’re back to this again.